Most people work a typical five-day, 40-hour work week. Some get paid weekly or bi-weekly but for most people they receive regular, scheduled payments for the work that they do. Now imagine working for months at a time and waiting for your pay-cheque to arrive, only to be paid nothing. For nearly three years, some members of the Epsilon Esports organization have faced this problem.

Epsilon Esports was created in February of 2008 and is a well established organization based out of Belgium. The organization is run by CEO and managing director, Greg Champagne. Epsilon has fielded teams in a variety of different games, including League of Legends, Counter-Strike: Global Offensive and Call of Duty, just to name a few.

In November 2016 an article was published by ESPN’s Jacob Wolf which stated that former League of Legends players for Epsilon Esports were exploring their legal options after failing to receive a total of US $24,986 in outstanding payments. In a statement to ESPN the five members of the team said, “Everyone in the team is owed one month’s salary by Epsilon Esports. We’ve tried to contact them over several months but have not received any response. We hope to find a solution to fix the issue.”

Max “Sartorius” Günther, Thomas “Kirei” Yuen, Sofyan “CozQ” Rechchad, Paweł “Woolite” Pruski and Lewis “NoXiAK” Felix never received an initial payment from the Belgian organization, which was promised. After competing in the European League of Legends Championship Series throughout the summer of 2016, the team was paid for the months of May, June and July, but the team hired New York attorney Roger R. Quiles to help them receive their first month’s pay.

Two and a half years later, in April 2019, I had the pleasure of speaking with former Epsilon Esports support player, Lewis “NoXiAK” Felix.

“They still owe us money. They threatened to sue us if we went public then we discussed going to court but decided it wasn’t worth the effort. It was hard to find an attorney who is close to esports and familiar with Belgian law. He [Quiles] had several talks with them [Epsilon] but they didn’t come to any agreement. He told us that it might take several years if we go to court and we would have to pay for the process,” Felix said.

When the organization threatened to sue the players if they went public, they were bluffing. The article was published by ESPN, but Epsilon did not launch any count.

“They were just bluffing and trying to scare us,” Felix said. “The owner of Epsilon said that we should be happy that we got paid anything since we didn’t win the tournament.”

Epsilon responded to the allegations made in the article in a statement, which has since been removed from their website, stating that they had honoured the terms of their agreement with the players.

“We do believe that we paid a very competitive salary (with huge bonus), and that we paid it for the period we agreed upon with the players,” the statement said. “Fair player treatment is very important to us, and therefore we even provided a gaming house to them as comfortable training grounds.”

Epsilon Esports was contacted regarding the situation but they were not available for comment.

The organization’s disastrous fallout with their League of Legends team was yet another smudge on their record. Epsilon also allegedly failed to pay the players on their Xbox One Smite roster after the team placed third at MLG’s Pro League Tournament, according to a report by GameSkinny.

It didn’t help that at the start of 2016 Epsilon had also lost their Spanish Counter-Strike: Global Offensive team. In January 2016 the team spoke with HLTV.org and released a joint statement revealing that, “they had grown unhappy at the lack of support provided by Epsilon, who allegedly failed to deliver on a number of promises made before signing the team in May.”

The article goes on to explain how each player on the team is owed a four-figure fee and that their attempts to receive the money, which included travel costs and tournament fees, led nowhere.

“We have made the decision to leave Epsilon way too late, despite the fact that they have not given us what was promised (bootcamps, paid expenses to an event in the United States, full gear support, ESEA premium, etc),” the team told HLTV.

“We paid for the last months of ESEA Premium and for tournaments’ entry fees ourselves. We have had the same jerseys for almost nine months, and these are not even the official club jerseys. They are low cost jerseys that were shredded after a few months. They told us for three months that they would send us new ones, but they are still on their way. For every tournament we attended, they said they would buy the tickets, but then on the eve of the event we had to buy them ourselves.”

The team claimed that it wasn’t just one event where this happened, but it seemed to be the case for every tournament.

“When it comes to salary, they paid it when they felt like it. MusambaN1 was at Epsilon for five to six months, and he spent most of that time asking for his contract to be sent to him so that he could start getting paid. His contract was not sent until a few weeks ago. Epsilon did not even give us a server to practice, we had to buy one ourselves,” the team said in the HLTV article.

“We are very sad for this situation and without motivation to continue to compete under this organization, despite the good name they have in the scene. We have not achieved the goal of being a top team, but that is not a reason for players not to be treated fairly,” the team added.

The Spanish roster consisted of Francesc “donQ” Savall Garcia, Alejandro “ALEX” Masanet, Omar “arki” Chakkor, Aitor “SOKER” Fernández and Jonathan “MusambaN1” Torrent. All five players have found different teams to join since their departure from Epsilon.

After their public fallout with the Spanish CS:GO roster, Epsilon Esports managed to stay away from any negative press. That was until they failed to pay Team Endpoint for the transfer of player Owen “Smooya” Butterfield to a German esports organization named BIG in April 2018.

A Tweet from Team Endpoint CEO, Adam Jessop, stated that the issue had still not been resolved in August of that same year. Jessop had contacted them with multiple emails before posting to Twitter about the situation.

I spoke to Jessop regarding the money owed but he was unable to comment in any official capacity due to contractual agreements that were in place with Epsilon.

“The issues we had with them are well documented publicly due to them failing to meet their contractual obligations regarding a ‘sell on’ clause which was in place and the fact I tweeted about this at the time to try and bring light to the issue and get some closure on the issue after waiting for several months.”

With Epsilon back in the press for the wrong reasons, the floodgates seemed to open yet again.

In August 2018, an article released by DBLTAP, stated that French Street Fighter V player, GDMKuja was allegedly owed money for several month’s work. The player addressed the issue via Twitter, stating “Epsilon are months late into my salary and now they are saying they won’t pay me besides the Gfinity month while I have a one-year contract which says they will pay me every month.”

In September 2018, two of the players on their Call of Duty roster took to Twitter about their lack of payments from the organization.

Jordan “Reedy” Reed and David “Dqvee” Davies joked about how they wanted to play wager matches but they were unable to without having received a payment from Epsilon “in so long.” Two months later Davies would leave the team to join the English organization, Lightning Pandas.

To start off 2019, yet another Epsilon Esports team was facing similar problems. Rocket League player, Daniel “Cheerio” Björklund took to Twitter, stating that he was leaving the organization.

In April 2019 I was able to speak with Björklund’s former teammates, Bram “Bilbo” Vanoverbeke and Sebastian “Sebadam” Adamatzky about the situation.

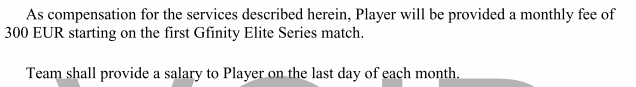

“We did sign a contract and it specifically said that the team was to be paid on the last day of the month during our three-month stay with them,” Vanoverbeke said.

“Most of the prize money didn’t go through Epsilon so that was not usually a problem, but our salaries kept getting pushed back and a month after our contracts ended I got sick of it and threatened to take legal action. They then paid everything they owed us. I think it took less than 24 hours after I sent an official email.”

Vanoverbeke said the organization is disorganized at times.

“The AirBnbs they booked were cheap and the travel was usually late. I even had a case where the ticket wasn’t in my name,” he said, when referring to a Eurostar trip from Brussels to London. “I still got on but it was as if they didn’t even bother checking who they were sending.”

“As for the hotels, I actually was not placed in any during the Gfinity Elite Series because I lived close enough to where I was happy to take the train to London on the day of the tournament. However, I would agree that the AirBnb that was booked for me and Cheerio during the Paris Games Week ESL Rocket League tournament was not the best as it didn’t have enough beds for the amount of people who were staying there from other Epsilon-sponsored games. But we only had to stay there one day so it was not that big of an issue for me,” Adamatzky said.

He agreed with his teammates that Epsilon didn’t necessarily refuse to give them the money but the fact that they kept delaying the payment and saying that they would get paid next week every time they asked was frustrating.

“However, it didn’t make me feel bad in any way since with my experience with Ares esports I knew that you could probably get the money after a long while (although probably not all of it) as long as someone is trying to actively do so. And even so, money isn’t something that I play Rocket League for as I’d always play it competitively even without any,” Adamatzky continued.

He believes that although they had to wait to receive their money, he learned a valuable lesson.

“I don’t have any particularly hard feelings towards the organization as it taught me what I should be looking for in an organization in the future and what to stay away from if possible. But overall, I don’t have any hard feelings against them as they did pay us in the end, although I was paid less than the contract stated.”

Luckily the players were able to remain professional and continue to perform well in the Gfinity Elite Series throughout the entire situation.

“It actually did not affect the team atmosphere between Bilbo, Cheerio and me since we were performing well either way. It was just an annoyance that we had to bypass and try to fix which Bilbo was able to do with his letter to Epsilon which helped end the situation,” Adamatzky added.

History of esports

Although esports has seen rapid growth in the last five years, some say that the history of the industry dates back to the 1970’s, according to a report by Hotspawn. The first official competition took place at Stanford University on October 19, 1972, and saw students competing against each other in a game called Spacewar!. The winner, Bruce Baumgart, received a free one-year subscription to Rolling Stone magazine.

By 1980, esports competitions were becoming more popular when Atari held the Space Invaders Championship. Over 10,000 players competed in the event, making it the biggest gaming competition to date. This event also helped bring more attention to competitive gaming and establishing it as a mainstream hobby. 16-year-old Rebecca Heineman took home the inaugural event, becoming the first person to win a national video game tournament.

In 1980, American businessman Walter Day, created an organization called Twin Galaxies, which would track video game world records while also promoting new titles. These records would even be honoured by the Guinness Book of World Records, making gamers around the world fight to have their names engraved in the record books.

Things really began to pick up in the early 90’s, after Nintendo had released the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) in North America in 1985 and the Super NES (SNES) in 1991. The Sega Genesis also was released in 1989, creating competition between the two companies which ultimately helped create better games, while helping the esports industry take off.

Nintendo hosted the Nintendo World Championships in 1990 with the finals of the event being played at Universal Studios in California. In 1994, Nintendo hosted another world championship to help promote the SNES, holding the finals of the event in San Diego, California.

Throughout the 2000’s, games like Halo and Call of Duty dominated the esports industry in North America while the South Koreans were still competing in StarCraft related events. Prize pools were steadily increasing while more and more teenagers and young adults were putting more time into these games. Many events were being televised in North America, Europe and South America at this time as well but in 2011 esports fans around the world were offered a place to watch nearly every single future event. Twitch, formerly known as Justin.tv, was a website created by Justin Kan, Emmett Shear, Michael Seibel and Kyle Vogt in 2007 which would allow anyone to broadcast themselves doing just about anything on the site.

After a few controversial events took place on the platform, the site rebranded in 2011 and became what we now know as Twitch. Many developers and tournament organizers would pay Twitch to broadcast and promote their events so that fans of each title could easily access and view their favourite esports. The first ever League of Legends World Championship was held this same year and featured a $100,000 prize pool. Over 1.7 million viewers tuned in to watch European team, Fnatic take home the first ever trophy, according to the game’s developer, Riot Games.

Only a year later, the event would be hosted at the Galen Center in Los Angeles, California with 10,000 fans attending the venue with Riot claiming that the event was viewed by over 8.2 million unique viewers from online sources and television. The developers also increased the prize pool to a whopping $1 million.

In 2014, 27 million unique viewers tuned in watch the grand finals of the League of Legends Season 4 World Championship, with Samsung White taking home the lion’s share of the $2.13 million prize pool in front of roughly 40,000 fans at the Seoul World Cup Stadium in South Korea.

American pop rock group, Imagine Dragons, performed some of their songs which included the theme for the tournament, “Warriors.”

The League of Legends World Championship has continued to bring in these kinds of numbers each year and since 2016 the viewership has outshined viewership totals for Major League Baseball (MLB) and even the National Basketball League (NBA), according to Hotspawn. Last year’s event even provided the game’s largest prize pool to date with $6.45 million distributed to the 24 teams who participated. The winning team, Invictus Gaming, took home over $2.4 million alone.

Although League of Legends has been known to have some of the largest prize pools in the esports industry, their numbers pale in comparison to those of Dota 2. Developers Valve have created many popular games over the years including the Counter-Strike series, Half-Life series as well as both Portal games. Although Counter-Strike has seen massive viewership like League of Legends, neither game’s prize pools can even compete with Dota 2.

Since the Dota 2 International 2014, the prize pool for this game’s world championship has grown steadily each year from over $10.9 million in 2014 to over $25.5 million in 2018. Dota 2 has hosted the top five highest paying events in the history of esports and there is no sign that this will change any time soon.

Esports have come a long way since the 1970’s where arcade games had many kids, teenagers and young adults competing to beat each other’s top scores. There are still many games where individuals play against each other but many top esports now feature team-based gameplay. Tens of thousands of esports athletes are now competing across the globe in hundreds of different titles. With salaries ranging from thousands of dollars to millions of dollars, depending on the skill level of the player as well as funding from leagues, events and organizations. Sponsorships from gaming peripheral companies and mainstream media have brought copious amounts of money into the esports industry with some teams even receiving funding from traditional sports teams.

Many NBA and MLB teams and players have invested in the esports industry, forming partnerships with many gaming organizations. Even some massive soccer teams like Paris Saint-Germain F.C. and FC Barcelona have been testing the waters of the esports industry by sponsoring players and teams in many different titles. Esports sponsorships reached an all-time high back in 2017 when it was announced that multimedia entertainment conglomerate, Disney, would be investing in the esports organization Team Liquid, according to a report from Slingshot Media. The esports industry is continuing to grow each year, reaching astronomical numbers in terms of viewership and funding. It seems as though this upward trend is only going to continue with time.