Boom … boom … boom … swish … the echoes of the basketball hitting the freshly waxed court fills the gym like the beat of a drum in an empty arena. Shequell Gilgeous-Glasgow is a basketball player from Conestoga College in Kitchener, Ont. Every morning he starts his day the only way he knows how, playing basketball.

Standing 6’3, Glasgow is tall, athletic and usually towers over every other person. Seeing him walk through the hallways of the college, his head is above the busy crowd of students trying to make it to their next class. The 22-year-old has a very serious look on his face whether he’s on the court slicing through the lane for a layup, or just walking around town. A tough demeanour is something that comes with time.

At a very young age, before he could even hold the ball in one hand, Glasgow fell in love with the game.

“Since the age of four or five I believe, my dad put the basketball in my hands. It was like love at first sight to be honest. I got obsessed with both playing and watching the game,” he said.

Before basketball, he tried his hand at a couple of other sports before ultimately dedicating himself to his true passion.

“Actually, soccer was the first sport that I played at the organized level. I was good too, but I didn’t have the same passion and desire for it like basketball. I also tried karate for a little bit as well,” said Glasgow.

Coming from a family of ballers, his cousin, Shai Gilgeous-Alexander, is currently playing in the NBA for the Oklahoma City Thunder and is becoming one of the best young players in the league. Glasgow himself is a skilled player. He is currently third in the Ontario Colleges Athletic Association in scoring, averaging 21.9 points and six rebounds in his last season with the Conestoga Condors. He has hopes of continuing to play the game he loves and to sign a pro contract.

“My plans are to keep working on my skills and mindset in the game and hopefully sign a pro contract in the near future,” he said.

Glasgow and his cousin are prime examples of how basketball has grown in this country. Although they had different journeys, they both started the same, as Canadian kids who fell in love with the sport. Shai went to a high school in the United States to play ball and ended up playing for the Kentucky Wildcats, but having to go down south to get recognized by a NCAA team just isn’t the case anymore. Here in Canada, basketball academies are popping up all over the country.

Down a long country road with farms on both sides is a gym where some of the best youth basketball players in Canada go to play, the Athlete Institute. The smell of manure is pungent, as if cows have set up camp in everyone’s nostrils. Inside, the smell is much better, although when the courts are full of some of the most sought after basketball phenoms in Canada, it can stink of perspiration. The Athlete Institute is home to one of the greatest basketball academies Canada has to offer, Orangeville Prep. Here is where NBA players like Jamal Murray and Thon Maker honed their skills and made it to the big league. The sound of bouncing basketballs and yelling coaches echo across the court like they’re on a loudspeaker. The high pitch noise of shoes on the hardwood is like a hundred cabinets with squeaky hinges.

Players from all across the country come here for a chance to be the next big star, but first they have to go through Alex Dominato, athletic administrator in charge of recruitment. Dominato is an average looking guy whose thin glasses just cover his eyes. He is very passionate about finding the best basketball players Canada has to offer and isn’t afraid to speak his mind. His stern approach will leave no doubt in a player’s mind if his application is accepted or denied.

The sport has grown so much in Canada that the institute has even gotten international attention because of its player growth potential. Dominato is also in charge of accepting and reviewing international applications.

“They (applications) are from people from all over the world who are looking to attend our prep school and want to learn more. I’ve got two calls today, speaking with families. One’s Canadian, but another one’s from Hong Kong. They’re calling from all over the place. I’m usually speaking on the phone with someone from South America. I’m talking to somebody from some continent every week, so in terms of growth it’s definitely there,” said Dominato.

The country of the great white north is not only being known for producing hockey superstars but now high-quality basketball players at all levels. NBA stars like Andrew Wiggins, Tristan Thompson, Jamal Murray and Glasgow’s cousin Shai Gilgeous-Alexander are becoming well known around the league and creating waves, waking up the rest of the world to the new age of Canadian superstars.

In the last few years, basketball has taken off in this country like Michael Jordan from the free throw line. This rapid growth can be attributed to a number of things. The Toronto Raptors have been consistently good, making the playoffs for six consecutive seasons. They were even crowned NBA champions in 2019, marking the first title win outside of the USA. The number of successful Canadian players in the NBA has also served as notice that this country is a hotbed of talent.

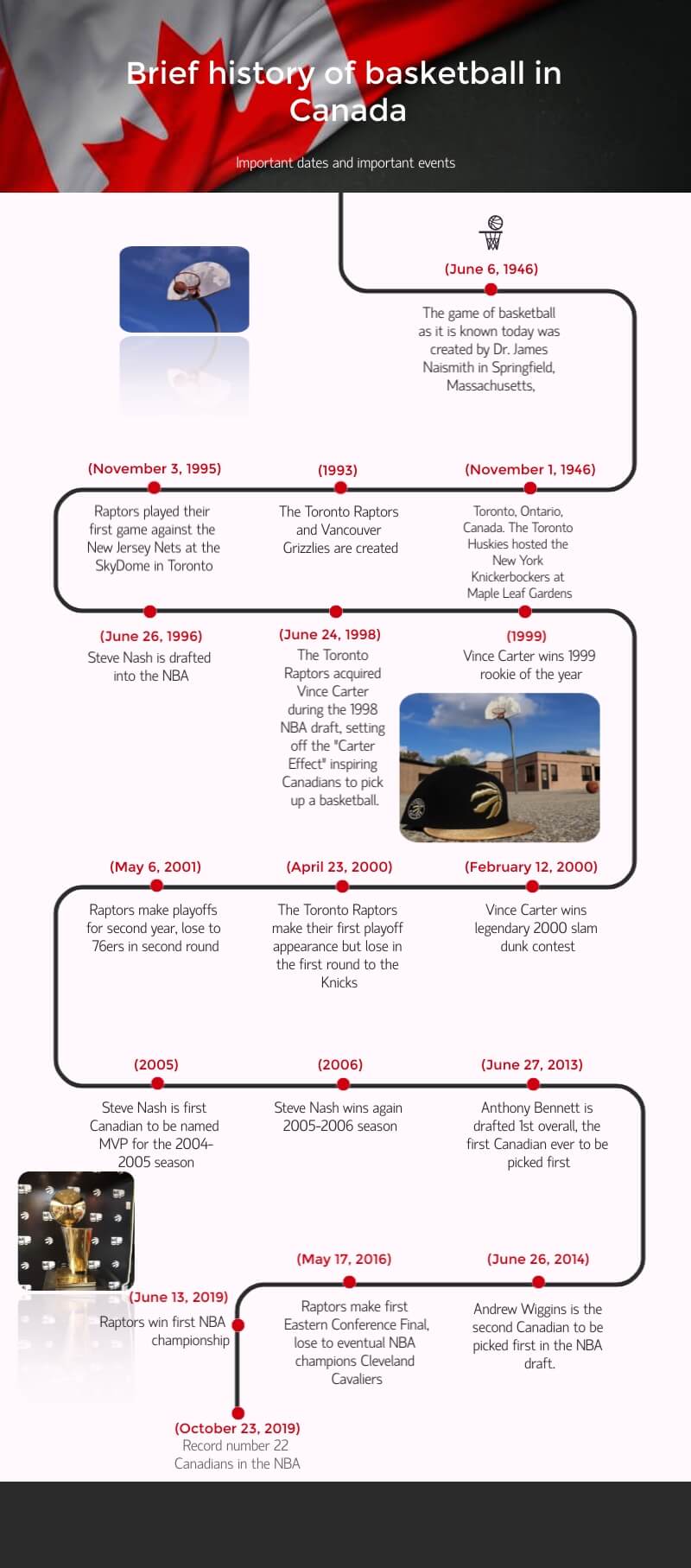

Even though basketball is gaining massive national popularity now, there has always been a large following of the sport in this country. Hell, the guy who invented it was Canadian. Another deep-seeded root is the teams playing in Canada. Since 1995, the Raptors have called Toronto home, and at that time Vancouver also had an NBA team, the Grizzlies. With the new Canadian additions to the NBA and rising superstar Mr. Air Canada himself, Vince Carter, a new generation of basketball lovers was born. Many of the current NBA stars from Canada grew up watching players like Carter, Steve Nash and Tracy McGrady dominate in the league. This gave youth hope and planted the idea that one day, maybe they too could play in the pros and leave their mark on the game. This has also led to the average fan, fanatics and everyone in between all falling in love with the game. Blake Murphy is one of those people. He started writing about basketball as a hobby and turned his passion into a career.

Murphy, from Toronto, is a normal-looking guy with a finely trimmed beard. He always looks like he just left a barbershop. He started his professional writing career at TheScore, a Canadian-based digital media company. He also runs a popular Raptors blog called Raptors Republic, and has been doing so for years. His way with words makes even the novice fan understand the complexity of the sport and brings a unique analytic side to most of his stories. He thinks that the increase in Canadians playing at high levels such as the NCAA and NBA has to do with the “Carter Effect.” This phenomenon is best described as the impact Vince Carter had on Canadians (especially younger people) while playing for the Toronto Raptors.

“I think we’re seeing kind of the second wave of the so-called Carter Effect. The introduction of the Raptors, the popularity of Carter and Steve Nash’s time at the top of the league all happened one after the other to where there’s an entire generation of young Canadians who would have had multiple entry points to the sport,” said Murphy.

As of now, there are 22 Canadians in the NBA, the most ever in the history of the sport. Canada also has the most players in the NBA besides the United States. The representation young players have now has never been seen before. Kids from Kitchener who watch Jamal Murray play on TV will have proof that a kid from their city can make it to the NBA. Murphy said those in the league now will normalize the idea of the Canadian player.

“As the first wave of those inspired by basketball in Canada began to see some success, there was now representation, too, where Canadians making it in basketball was less and less of an anomaly, and that inspires even more players coming up,” said Murphy.

Not everyone can be a superstar and Dominato thinks younger players are waking up to the fact that it’s OK to just be a role player.

“There are a lot of really good guys who can maintain themselves and stay on NBA rosters. So I think the increased depth of Canadian players is what the major change has been over the last couple of years. You really start to see Canadians start to understand that it’s not just all about being the superstar,” said Dominato.

Although sports like soccer and especially hockey have been big in Canada for generations, hockey is one of the biggest defining cultural Canadian stereotypes. Now basketball is becoming mainstream and starting to capture that cultural spot among many youths in the country. Although it hasn’t dethroned that top spot, that image of an apologetic Canadian playing hockey and holding a Tim Hortons coffee is still the picture most of the world has of this country – for now.

According to the International Ice Hockey Federation, there were 621,026 registered hockey players across Canada in the 2018/2019 season compared to 721,504 players in 2014/2015. In comparison, in 2014, there were 354,000 basketball participants according to the 2014 Youth Sports Report.

There are many factors why hockey is declining in terms of the number of participants. Some attribute the decline to price, safety and a changing culture. In an article in the National Post written by Richard Warnicka, he said that the game is stuck in the past and all of the ugliest sides of hockey are being brought to the forefront. Allegations of bullying, mind games, racism and violence have been cited as some of the most toxic elements of hockey culture. This comes after remarks from one of the most prominent voices in hockey, Don Cherry, and his now infamous rant about “you people.”

“From the lowest levels up to the pros, hockey in Canada is in crisis,” warns Warnicka.

“The sport has been tagged, rightly or wrongly, as too expensive, too old-fashioned, too self-serious and unwelcoming. Minor hockey comes off as a kids’ game played for the benefit of adults. In the NHL, fun still seems like heresy. Overall, the game gives the impression, too often, of a pastime that’s caught in the past,” he said.

In his article, he interviewed Amy Stuart, one of only a few female head coaches in the Greater Toronto Hockey League. “In some ways, I feel like the hockey rink and the locker room are almost 20 to 30 years behind in terms of what’s acceptable,” said Stuart.

This isn’t to say that Canada’s frozen pastime is ignoring the signs and calls for change. Many inside of the community and at league management levels are acknowledging the problems with being inclusive and the changing demographic of the country. In a large, shiny arena located in Kitchener, Ont. is the Kitchener Minor Hockey Association office. Here is where Rolland Cyr, general manager of the KMHA, can usually be found. Cyr is unmistakable. He has a salt and pepper goatee, glasses and a booming voice. He recognizes the issues within the hockey community and is working on creating a different culture, making all feel welcome.

“I think Canada is an ever-evolving and ever-changing entity and hockey is adapting to meet that need. Has it adapted in advance, no,” said Cyr.

Erika Wittlieb/Pixabay.

It’s no secret that the number of kids playing hockey just isn’t what it used to be. Cyr says there is definitely a drop in the number of players in the past couple of years and some associations have been hit harder than others.

“You see a general number drop off, not as severe in Kitchener, but in many places. We have a fairly robust program, but there is still a drop. I think as we are adapting and trying to find new and more inclusive ways to ensure we are including everybody, we will strive to be the best program we can be. So while numbers aren’t the only indicator, they are one,” said Cyr with passion.

Another reason for kids not playing hockey is the price. It is one of the most expensive sports in terms of money and time. To put your child in hockey, you need to buy all the necessary gear such as skates, pads, sticks, hockey bag, helmet and the uniform. According to a study done by The Globe and Mail, on average it costs around $1,200 to $3,200 a year to have your kid in hockey. The older your kid is the more expensive it becomes. For sports like basketball and soccer the only equipment you really need is proper shoes and possibly a uniform.

All sports require some form of commitment and require the athlete and usually their parents to go to practices and games. Minor hockey averages around 30 games a season where minor basketball is around 20 games. There is also a more lucrative tournament system for hockey players which require more time on the road.

There are many organizations and charity foundations that help parents when it comes to affording hockey equipment and admission prices. Kitchener Minor Hockey works with a charity called Donna’s Kids, and they provide confidential financial support to families who couldn’t otherwise afford hockey equipment.

“We don’t want any kid being held out regardless of economic circumstance and we want them to play at the level their physical ability dictates. We have about 130 kids a year sponsored through Donna’s Kids and we do over $120,000 worth of expense around them alone,” said Cyr.

The price is such a big factor that it can turn players off from the sport entirely. Murphy recalled his own history with the sport and growing up as a hockey kid.

“I came up as a rep hockey player and vividly remember the conversation with my parents where I had to decide whether to go down to house league or keep paying for it myself, because I wasn’t going to make junior and it wasn’t worth the cost in a family with three kids. And this is in a mostly middle-class, smaller-town family. Hockey is a sport of privilege now, which is why I think you’ve seen a transition to greater enrolment in basketball, soccer, swimming and other sports with lower barriers to entry,” he said.

Another reason for the spike in basketball admissions and the drop-in hockey is Canada’s ever-changing demographic. This country is one of the most multicultural places in the world and prides itself on that. As people come to this country, they weren’t ingrained with hockey is the must-play sport and it opens them up to exploring their options. Murphy has seen this play out first-hand.

“As demographics change, there are maybe fewer people who were born into or raised in the Canadian cult of hockey. For first and second generation Canadians, that natural assumption that everyone will play and breathe hockey maybe isn’t there, and then sport decisions become about a multitude of factors instead of cultural inertia,” said Murphy.

Although there are different viewpoints when it comes to whether or not hockey is able to adapt to the changing demographic and appeal to those who are not traditionally hockey players, Cyr is confident in the sport’s ability to pull in second or third generation Canadians.

“Statistics are already showing that it’s second and third generation immigrants who are picking up hockey. As Middle Eastern and Asian immigrants are settling and hitting that second and third generation, they’re looking for other things to do. You’re going to see more and more participation and we as hockey programs have become more astute to how to speak to our population that’s out there,” said Cyr proudly.

Although minor hockey says they are able to speak to the multicultural population, historically the sport has been mainly white players with little diversity. For years, as the racial makeup of the country has changed, the sport has come under fire and been questioned about its inclusivity. With sports like basketball, there is no question about racial diversity and representation. Visual minority players in the NHL have come out and talked about their experiences while playing the sport.

Former Calgary Flames player Akim Aliu made headlines in 2019 when he accused then Calgary head coach, Bill Peters, of directing racial slurs at him in the locker room. Peters handed in his resignation four days after being accused. In an interview with The New York Times, Aliu detailed some of his experiences with racial abuse.

Aliu thinks he was around 12 or 13 years old the first time he heard a racial slur directed at him while playing hockey.

“It starts really early,” he said. “With parents I had a couple of incidents where people would yell racial swears while I was playing. I was old enough to understand exactly what was being said.”

It seemed like everyone was yelling insults at him, from players on the opposing team to fans in the stands.

“You notice really quickly that you stand out when you’re a minority player,” he said.

When it comes to sports, there are so many options in this country. The ones that will survive and thrive will be the ones that can adapt to the changing landscape of society. Another factor is how easy is it to just pick up the sport? Cyr said hockey is one of the hardest sports to learn. You are trying to learn a completely unnatural skill – skating. The act of gliding around on ice on thin metal blades is a lot harder to learn than simply running. Glasgow thinks basketball is so big because anyone can walk off the street and pick up a ball.

“I feel like a lot of people will play more pick-up basketball because it’s the easiest pick-up sport to play. Many rec centres have nets in their gyms,” said Glasgow.

Basketball just keeps on growing in this country, but regardless of hockey’s troubles and controversies, it will always be the cultural sport of Canada. Even if basketball becomes the most popular sport in the country, hockey will forever live on as a part of Canada’s identity, like a face tattoo for the world to see.